DIVING IN THE MOON

HONORING STORY, FACILITATING HEALING

Stories That Spark Reflection

© Faye Mogensen

For some of us, hunting for stories is both a passion and a necessity. Having stories in hand is vital for performance and workshop requests – but that’s not all. When feeling challenged by new situations, having a story to reflect on can be hugely valuable in helping guide behavior. When grappling with best responses to difficult circumstances, having a story to share can help pull us all out of a rut.

By way of example, consider the current situation of refugees, undoubtedly one of today’s big issues and one that is not likely to go away. In 2007, Scientific American reported, “As global warming tightens the availability of water, prepare for a torrent of forced migrations.1” Already, increasing numbers of refugees are arriving in the global north from countries in Africa as well as the Middle-East. Of course, we all know that the war in Syria is causing the mass exodus from that fair land. But what caused the war? It is a complex situation and there are many factors at play but, in 2015, multiple journals2 and the National Academy of Sciences concluded that drought in Syria, exacerbated to record levels by global warming, pushed social unrest in that nation across a line into an open uprising in 2011. It seems that climate change can be the straw that breaks the camel’s back.

What are we in the global north to do? And how can stories help?

One obvious answer is to continue to lobby our governments to honor agreements made at the Paris Summit on Climate Change, and to encourage others to do so by lifting up concerns about the environment and our relationship to it. Stories like To Whom Does the Land Belong 3 (a story from the Middle East about our relationship to the place we call home), or Baldy 4 (a story from Scandinavia where the main character’s quality of life improves when he “listens” to his surroundings and treats them well), might help begin that conversation. Another answer is to work on opening our minds to the notion that the current wave of refugees is only the beginning. Milk and Sugar 5 (a Parsi story about migration and resettlement, where two cultural groups agree to tolerate and accept one another while maintaining their different religious practices) is one example of a folk tale that could be a springboard for conversation. A third answer, and the one I want to explore here, is to work on opening our hearts so that we can truly welcome new arrivals.

When I consider my experience of the generosity of strangers, I am awed that many of those strangers are from amongst the poorest people in the world. I shouldn’t be surprised. Generosity Bends the Road 6 is a story from Sudan that offers insight into the culture of generosity that continues to thrive there today, and is an inspiring example of the transformative power of radical generosity.

Generosity Bends The Road

A man named Attay lived far off in the countryside. He lived there with his wife, his seven sons and their wives, his nine daughters and their husbands, plus sixty-three of his grandchildren and great-grandchildren – some of whom were married. The family on its own was an entire a village. Life was good for Attay and all his offspring.

They were able to grow or hunt the food they needed, water in the river was plentiful, and there were trees and wood enough to build and heat their homes.

Now and then, they traveled the long road into the city to trade some of their goods for treats like sugar or ready-made cloth. But mostly, they stayed home and enjoyed life there.

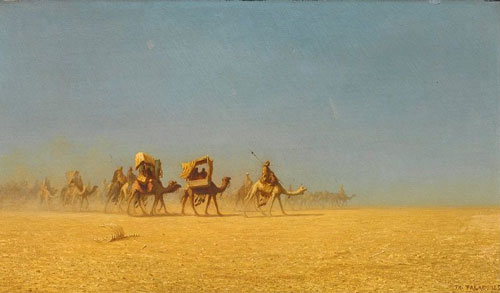

The village was situated next to the river and far from the caravan road. It was very rare for visitors to come by.

But one day, not far from the village, a caravan of a dozen merchants lost their way. Many days passed as the men wandered about. The forest was dense, and they couldn’t tell where to go. Sometimes they circled back to where they’d been before. They were growing increasingly worried.

Finally, very early one morning, the merchants awoke to the sound of roosters crowing. It was at some distance and like music to their ears!

They saddled up their camels and loaded their belongings as quickly as they could. By the time they mounted, they could hear the faint sound of dogs barking. More music!

They moved toward the sounds; by sunrise, they could see faint lines of smoke rising into the sky. It could only be a village!

They urged their camels on.

When at last they arrived in the village, they were met by several young men.

The men were smiling and welcomed them warmly. They guided the merchants into a yard where they tied the camels and offered them grass, grain, and water.

The merchants were invited into another yard and welcomed by an elderly man—none other than Attay. He joined twelve young men in offering karama to each of the merchants.

In Sudan, karama is the traditional offering given as thanks to Allah for a wedding celebration, the birth of a child, or the return of a loved one who has been gone a long time. It is also the traditional offering to a guest. In the old days, as in this story, karama was a sheep that was slaughtered to feed the guest, or for Allah to feed the poor. Today it is still often a sheep, but it might also be some other kind of food like cooked millet or sorghum.

Attay and his family offered karama to each and every one of the twelve merchants, in the form of twelve sheep. According to tradition, the merchants each jumped over their karama sheep. After that, the feasting and celebrations began. The villagers and their guests shared food and stories and songs, praising and glorifying Allah and the Prophet (Peace Be Upon Him).

The villagers made the merchants feel at home and welcomed them to stay for several days until they and their camels were well rested. When at last the merchants were ready to resume their journey, they offered Attay gifts. He refused.

The name Attay means giver, and it was his honor and privilege to be able to host the merchants. He invited them to return again and bring other guests with them.

The merchants were appreciative of the fine treatment they had received from Attay and his family. As they continued their travels, they spoke highly of the experience. They remembered the standing invitation, and within the year, they returned with more men.

Their reception was as warm and as generous as it had been the first time.

After that, stories of Attay and his family spread like fire in dry grass. Anyone traveling along the caravan road turned off to visit. Year after year, more and more people came.

Finally, the stream of visitors was so frequent that the route to Attay’s village became more visible and distinct than the main caravan road. The former route all but disappeared.

The village of Attay came to be the most important station along the caravan route. All who stopped by were served with the same generosity as the first visiting merchants. All the food and any supplies they needed, a room to sleep, and care for their camels was provided at no cost.

Attay came to be called Awaq Addarib – the one who bent the road. His story is shared to this day in Sudan. The Sudanese continue to offer the same kind of generosity to strangers.

I wonder how many roads have been bent in this way and whether we might be able to bend one too?

After telling a story like this, engaging listeners in reflective questions can help them tap into their own experiences of generosity, and their wisdom about how to encourage and spread it. Questions I’ve asked listeners include:

- When have you noticed a dramatic change that came about because of generosity?

- What were some of Attay’s rewards for his generosity?

- What are some of the rewards you have experienced when you have been generous?

- Do you know of other roads that have been rerouted in a similar way?

- How might we ‘bend’ a road towards our home?

Despite our best intentions, we tend to resist change. Fear is one of the factors that might prevent us from trying to ‘bend the road’ and encourage people in need to move to our part of the world. Cooking Together Trinidad Style 7 is a story that illustrates diverse cultures overcoming their fear of one another as well as their fear of change.

Cooking Together, Trinidad Style

Callaloo is a thick green soup. It’s eaten in places like Jamaica and Trinidad where people say that learning to make Callaloo soup is a little like learning to live.

The soup goes way back in time, to the days when the ports of Trinidad were full of tall sailing ships. The local Carib and Arawak people weren’t sure what to make of them. Some had sailed from Britain, and others were from France and Spain. The new arrivals included people from China and India, Ghana and Mali. They came from Syria, Portugal, and Venezuela too.

Each of the groups arrived on the shores of Trinidad with their own language and songs, their own clothing and food, different from each other and from the people who’d lived on the island forever.

People are people; we’re most comfortable with what we know. So even though Trinidad is not a very big place, people stuck closest to their own kind. The Arawaks and Caribs retreated to the forests. The Chinese avoided the French, who avoided the Indians, who mixed as little as possible with the Venezuelans, and so on down the line. Trinidad was a divided nation.

Things might well have stayed that way. But one rainy season, the hurricane trail took a turn toward Trinidad. The storm raged like a beast trampling over the island, tossing and turning everything up.

When the beast finally moved on, all of Trinidad was a terrible mess. Crops were drowned, houses flattened, trees uprooted, and boats smashed to smithereens. The people who survived were scared, and hungry.

When the beast finally moved on, all of Trinidad was a terrible mess. Crops were drowned, houses flattened, trees uprooted, and boats smashed to smithereens. The people who survived were scared, and hungry.

You know how it can be when there are shortages – the ugly in us can come out. Sure enough, people grew greedy. It was hard for them to find food, and when they did, they hoarded it for themselves and their own kind. Worry, anger and jealousy hung over the island like a great black cloud. And the island was more divided than ever.

It might well have stayed that way, but an elderly woman happened to notice something glinting beneath the ruins of a house. What was it? She was curious. She began to pull away the boards and rubble. They were heavy. She had to work hard. Finally, there it was, a great huge cooking pot. The woman looked at it.

“Mmmmh?” she thought. As she began to hatch a plan, a big smile came over her face. She lit a fire with some of the boards and rubble. She filled her pot with water, added some salt, and began to stir and chant.

“It may be a little bland, but the soup I’m cooking is for every child, woman, and man.”

Her chanting was heard far and wide. People grew curious.

“It may be a little bland, but the soup I’m cooking is for every child, woman, and man.”

No one wanted soup that was bland! Those who heard, hurried home to search through their store of goods.

A Carib family arrived in the square with sweet cocoplums and starchy cocoyams. The woman smiled as they peeled and then plunked them into the pot. An Arawak family followed suit, with fine bud peppers and slices of sweet squash. A family from Mali brought bunches of green okra pods that had survived the storm. A British family delivered salt-pork. An Indian family had found coconuts knocked to the ground; they cracked them open and poured the sweet milk and shavings into the soup. Syrians added cumin, while the Spaniards and French came with garlic, onions, and thyme. A Chinese family contributed the big green leaves of dasheen. They tore the leaves into strips that gave the soup its beautiful deep green color.

Soon the aroma coming from that pot caused people to hum and smile. The smart woman stirred. Her soup was almost finished. She paused for a few moments, curious about the clamor of children she could hear down at the beach.

A short time later, a big giggling mixed group arrived—they were all colors and shapes and sizes. They’d been too busy helping one another capture crabs to pay attention to cultural differences. They had buckets full of rich-tasting blue crabs to add to the soup. The smart woman stirred.

At last, she announced, “The first ever… Callaloo!”

The old woman ladled out scoop after scoop of the mysterious mixed-flavor soup into people’s bowls and calabashes and cups. It was delicious and hearty! Once their bellies were full, they began to talk and tell stories. They began to sing.

After a while, some of them looked up. They saw that the big black cloud that had been hanging over Trinidad had parted. The skies had opened up and the sun was shining again. The cultural divisions on the Island of Trinidad were breaking down.

It’s said that the children who made the first ever Callaloo Soup continued to mix and mingle. It is said that their children were the Callaloo children – children who knew how to get along with people of all cultures, colors, shapes, and sizes.

I say the world needs more Callaloo soup and Callaloo children!

Questions to help spark reflection include:

Questions to help spark reflection include:

- When has a crisis brought out the best in the people around you?

- When has one person made a difference in your life?

- When have you been aware of the younger generation leading the way?

- When have you experienced a situation where people have worked together to create something out of nothing?

- When have you experienced people overcoming their cultural differences, and what helped them to do so?

- How does having less inspire more creativity? What is an example from your own life?

As the conversations grow, perhaps more of us will feel able to open the door to the many strangers who may come knocking in search of cooler climes, abundant water, peaceful communities and new friendships. The process of story reflection can be truly transformative – by choosing stories that describe the kinds of behavior we wish to emulate, we support one another in opening the door to better ways of being.

1 http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/climate-change-refugees/

2 http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/climate-change-hastened-the-syrian-war/ , https://climateandsecurity.org/2012/02/29/syria-climate-change-drought-and-social-unrest/ and many more

3, 4, 5, 6, and 7. To Whom Does the Land Belong, Baldy, Milk and Sugar, Generosity Bends the Road and Cooking Together, Trinidad Style are four of the folk tales in Ancient Stories for Modern Times: 50 Short Wisdom Tales for All Ages, published by Skinner House Press in 2016 (see bio).

Faye Mogensen has an M.Ed focused on Storytelling for Environmental Change. She has been telling stories professionally for almost 30 years. Currently, she runs the Children’s Spiritual Exploration Program at the Unitarian Church of Victoria where she often uses the lens of traditional folktale to spark explorations of our relationship with nature, with one another and with ourselves. Her recent book, Ancient Stories for Modern Times: 50 Short Wisdom Tales for All Ages (available at uuabookstore.org) contains a broad selection of traditional stories, augmented by reflective questions to help explore their diverse themes. www.fayetales.com, [email protected]

Faye Mogensen has an M.Ed focused on Storytelling for Environmental Change. She has been telling stories professionally for almost 30 years. Currently, she runs the Children’s Spiritual Exploration Program at the Unitarian Church of Victoria where she often uses the lens of traditional folktale to spark explorations of our relationship with nature, with one another and with ourselves. Her recent book, Ancient Stories for Modern Times: 50 Short Wisdom Tales for All Ages (available at uuabookstore.org) contains a broad selection of traditional stories, augmented by reflective questions to help explore their diverse themes. www.fayetales.com, [email protected]