DIVING IN THE MOON

HONORING STORY, FACILITATING HEALING

Paperman Jack And The Origami Mommy

© Megan Hicks

“Forget not to entertain strangers, for some thereby have entertained angels unaware.” New Testament, Hebrews 13:2

That happened to me in the 1980’s. It almost DIDN’T happen because I thought it was just going to be another obscene phone call.

I’d been getting them all summer, so when I picked up and heard, “Uh…is this the Origami Mommy?” I slammed the receiver down hard. “Origami Mommy.” That’s what the kids called me at the school where I worked. But school was out for the summer, and this guy wasn’t no kid.

Ten seconds later: RING!

“WHAT!?”

“Uh…is this the lady from the newspaper story…about origami?”

Oh. Well. Yes. As a matter of fact, it was. The local paper had just run a feature on Japanese paperfolding, and seeing as how I was the only person interviewed who spoken fluent English, mine was the predominant name cited. The writer was charmed with the “origami mommy” label the kids had given me.

“Yeah,” I said, “that’s me. Who am I talking to?”

“Uh…Paperman Jack Knutson. I been folding origami since fourth grade. I’m kind of a genius. I was thinking maybe you and me could get together some time and, you know, fold paper.”

I rolled my eyes and thought, Well, there’s an original pickup line. And I told myself, You don’t have time for this.

Truly, I didn’t. I was working six part time jobs, going to graduate school, raising my kids…

I told myself, Something about this guy is seriously off kilter. Tell him you’re too busy.

And I heard my mouth say, “Fourth grade, huh? Me, too! I was nine years old.”

It was my favorite Christmas present that year. An origami book, with little folded models pasted on the pages! But in 1959, among my family and circle of friends, nobody could help me with the diagrams. I was on my own. And here I was, thirty years later, selling my origami jewelry in New York and Santa Fe, still as obsessed with paperfolding as a nine-year-old.

He said, “Uh, hardly nobody even knows what I talking about…”

I could totally relate.

But I was so busy.

Still…

I had recently called the Origami Center of America in New York City, looking for a source of books and papers. I expected a receptionist to answer, “Origami Center. How may I direct your call.” Instead, I got a chirpy “Hello.” And I found myself talking to Lillian Oppenheimer, a woman whose name graced the foreword, the dedication, or the acknowledgements of every origami book I had ever seen. She was famous! And she talked to me that day for almost an hour. I thought, If Lillian Oppenheimer has time to make friends with a stranger making a cold call from Oklahoma City, I have time to meet with this guy. Once.

So Paperman Jack and I arranged a meeting. It had to be within walking distance, he said, because he didn’t drive. As it happened, in this city that ranks 8th largest in the U.S. in land mass – over 600 square miles – Paperman Jack and I lived less than a mile apart. We said we’d meet on Tuesday at 4:00, at Dunkin Donuts on 28th street.

When I got there, I stood in the glass-enclosed vestibule and scoped out who was sitting at the counter. The usual complement of cops, students, delivery men, and there, at the very end, a man hunched over a cup of coffee, folding paper.

An attaché case sat on the floor next to him. He wore brown wingtips. Chinos. A lab coat with a name badge over the pocket. A soft-looking young man, maybe twenty-five. Thinning hair. Freckles.

As I got closer, I saw that those wingtips were literally worn down at the heel. His pants were only almost clean. And the lab coat was actually a duster – one of those housedresses with snaps down the front, with a little Peter Pan collar. He had customized the name badge with a strip punched from red plastic tape: PAPERMAN JACK KNUTSON.

I cleared my throat. It startled him. He looked up with an expression that was an equal mixture of “deer in the headlights” and “delighted.” I held out my hand for a handshake.

“Paperman Jack. I’m the Origami Mommy.”

He gave me a soft, clammy handshake.

I sat down and ordered some coffee and launched into what I thought was going to be a short little charity visit. A mitzvah. I’d be outa there in under an hour. He’d be happy. I’d be happy. We’d go our separate ways. (I was so full of myself…).

I said, “What’re you working on?”

“Horse,” he said. “It’s not pure origami. You gotta make a couple of cuts. But it’s a good horse. It gots a story.”

Here, he reached for the attaché case, laid it on the counter, and pried the clasps with a plastic knife. I noticed his hands trembled. Inside the attaché case he carried a ream of dog-eared copy paper, a pair of black handled dressmakers scissors with one broken tip, a roll of Scotch tape, a little yellow stapler, random rubber bands, and a small bottle of Elmer’s School Glue. He noticed me scoping everything out and flashed a broad smile.

“Tools of my trade,” he said.

With the scissors he made a couple of cuts in the paper, returned them to the attaché case, clasped it shut again, and set it back down on the floor. Then he put the finishing touches on his horse. He was right. Even though it wasn’t “pure origami,” it was a good horse. It had good posture. It looked proud.

Paperman Jack walked the horse over to my napkin and reared it up on its hind legs. He pitched his voice low and said, “Hi. I’m Ed the Horse.” And then he looked embarrassed at his own silliness. “That’s dumb,” he said. “Excuse me.”

“You said the horse has a story?”

“Oh. Yeah. It’s my story, too…”

See, once upon a time there’s this horse – Ed the Horse. He used to be a racehorse but he tripped and fell one day and everybody didn’t like him anymore, and they decided to get rid of him. So they dug a hole and covered it up with branches and grass and said, “Here, Ed! C’mon, boy. We want to be your friend. See. We got carrots.” And they tricked him into stepping on the branches and stuff, and he in the hole. Then, everybody shoveled dirt in on top of him. They said, “We’ll bury him. Get rid of him.” Ed tried to climb out of the hole, but he slipped on the sides and landed back at the bottom. He tried to jump, but the hole was too deep. So he stomped his feet and said, “Quit it!” But they just kept shoveling. But then he noticed… when he stomped his feet, the dirt got hard under his feet. So he kep’ it up – stomping the dirt, stomping thedirt, stomping the dirt. And then the hole wasn’t so deep anymore, and pretty soon he stomped so much he was high enough to jump out and run away to a farm, where there was a boy named Erik who always wanted a horse and loved him and took care of him and they lived happily ever after.

“And how is that your story?” I asked.

“See, people used to call me Caveman, ‘cause I lived in a cave. I was homeless, didn’t have no friends, no place to live. Everybody thought I was crazy. I didn’t take a bath or cut my hair or nothing. I looked like a wild man. But then I started making stuff with origami, and other paper things, too, not just folded. I made a bicycle out of paper once. Pedals, wheels, handlebars – the whole thing out of paper. I couldn’t get on it, ‘cause it wasn’t strong enough. But the parts all moved. They put it in the window of the hardware store. When I lived in Leavenworth, Kansas. And a guy from the newspaper came and talked to me and put my picture in the paper… See! I’m famous, too. Just like you. But I ain’t rich. Are you rich? …Anyway, the newspaper guy called me Paperman, and now that’s my name. So what kind of stuff do you do?”

That day, Paperman taught me how to fold Ed the Horse. I taught him to fold something called a “Sonobe Unit.” Doesn’t look like much by itself, but with three of them you can make a pyramid. With six, you get a cube. With thirty of them, a stellated dodecahedron…and with more, the possibilities are limitless.

Three refills and two old fashioned donuts later I finally got up to go.

He asked if he could call me sometime and talk some more about origami.

My brain screamed, “You don’t have time!” and my mouth said, “Sure.”

During the next few days, four out of every five times the phone rang, it was Paperman.

“Hey, Megan, I got this idea, listen…”

“Hi, Megan, it’s Jack. I just made a soccer ball. All out of those Sonobe Units!”

“Hi, this is Paperman. I forgot to tell you this morning about this guy I met on the bus…”

By the fourth day, I finally said, “Look, Jack, I can’t spend a lot of time on the phone. What if you call me every two days — one time — and we talk for, I don’t know, ten minutes?”

And that was fine with him. He was like clockwork. Every two days.

Always, always, always he was discovering something — a new folding technique, the dumpster behind Kinko’s that was full of paper perfectly good paper — “It just gots writing on it, it’s not messed up at all!” — and it was FREE!

Like clockwork, ten minutes into the conversation, he’d say, “Okay, I’ll let you go now. Bye.”

Every month or so, we’d meet at the donut shop and…you know…fold paper.

I found out he was 24 years old. His mother still lived in Kansas with his step-father and was raising his sister’s children. She sent him a 60 minute phone card every month. His father was in Idaho. He would pay for a call on Christmas and once during the summer. One brother was in the Army in Alaska. One was in prison. I never was clear about how he got from Leavenworth to Oklahoma City. He lived in a supervised group home with half a dozen other men. He mentioned his social worker, a shrink, medications.

“You know what the meds are for?” I asked.

“Voices. The voices go away when I take my pills. There’s Thorazine and a couple other things. I got schizophrenia. I’m crazy. But I ain’t retarded. My IQ is 80-something and that ain’t retarded.”

One day when he called, he asked if I could come over to where he lived.

“I just made something incredible! I’d carry it up to Dunkin Donuts, but it’s pretty fragile.”

He lived in a neighborhood of big rundown rent houses that had been cut up into apartments sometime in the ‘60’s and neglected ever since. Students wouldn’t even rent there anymore.

The house’s single, feeble window unit merely circulated smoky, tepid air. Jack met me at the door and showed me into a large room where half a dozen inert adults slouched on unmatched sofas, smoked, and watched TV. Behind the sofas stood a table strewn with used copy paper (“Look!” He was all excited. “I found it in the dumpster behind Kinko’s. One side is completely blank! For free!”), scissors, tape and rubber bands. Paperman’s studio.

When he answered the door, the first thing he said was, “You know that Sonobe Unit you showed me? Well, they took us to the craft fair at Shepard Mall and this guy had these wood merry-go-rounds. I was talking to him about origami and how you don’t need to buy wood and power tools in order to make stuff. And he said, ‘Yeah, yeah. But you can’t make one of these outa no piece of paper.’ And right then and there I knew I could. Everytime, when somebody says, ‘Origami can’t do this,’ or ‘You can’t make a paper one of these,’ I just wait awhile, ‘cause I know I’m gonna get a vision that’ll show me how to do it. I’ll be right back.”

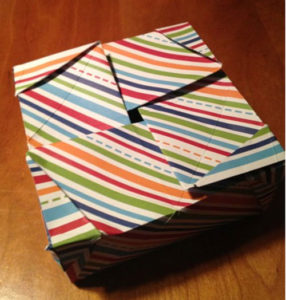

He ran upstairs and came down carrying… a paper merry-go-round. Four Ed the Horses pranced around the edge of a paper mat he had assembled from about sixteen sheets of folded paper. A rocket launcher mouthpiece made the center pole, from which the paper mat hung by kite string and paperclips. And the whole mechanism was mounted in the middle of the modular box I had shown him at our first meeting. Folded with trembling hands, it had the appearance of a picture out of focus. It was a rickety merry-go-round. But damned if it didn’t spin around and around and around.

“Pretty amazing, huh?”

All I could do was grin.

He said, “A lot of people think I’m retarded, on account I don’t read very good, and I can’t really write too good, either. But I ain’t retarded, ‘cause I can do this.”

As we were first getting to know each other, I was afraid that I was being tapped as an anchor, a lifeline, a savior…until I noticed repeated references to a fourth grade teacher who called to check in on him now and then, and sent him socks and underwear every few months. He mentioned a grade school principal who accepted collect calls and kept him supplied with postage stamps and postcards. An artist friend sent him art supplies every year at Christmas. He was friends with a children’s librarian who helped him find origami books. Gradually, I realized I was a Sonobe Unit — one piece in a support structure that Jack had managed to cobble together. He was taking care of himself.

His great ambition was to become a famous “origamist.” Everywhere he went, he struck up conversations with people and folded them things. On the bus. At the coffee shop. Maybe someday, he’d get discovered and become famous. He’d be rich enough to buy a car and learn to drive and make his mother proud of him. He’d buy a house where she could move in.

It was several months since our first meeting at the donut shop, when Jack called one night sounding … different. I couldn’t put my finger on it.

”I did something I don’t think I ever saw before,” he said. “I think it’s a brand new invention. And it’s pure origami. There’s no cuts. And I think it’s brilliant.”

He sounded subdued. Hushed. Almost reverent.

“What is it?” I asked.

“It’s a self-closing box. You gotta see it. You won’t believe it. It’s kinda hard. It gots four petal folds.”

Mastering a petal fold is what bumps a beginning folder into the “intermediate” origami skill level. In order to learn the petal fold you have to let go of your certainty that paper is a two-dimensional medium. You have to let the paper take you outside the box — literally. It’s the magic trick that creates appendages from which a folder can coax legs, feet, wings, heads, horns. I think Jack had mastered the petal fold before we met. I had certainly mastered it — years and years ago. But I never understood it at the depth he did.

Next time we met, he showed me his “pure origami self-closing box,” and I was duly impressed. The Friends of the Origami Center of America had just sent out a call for original models to be submitted for possible publication in the Annual Collection of members’ work. And Jack sent his box. Neither one of us could figure out how to diagram it, though — and diagrams were a requirement for submission — so we sent about a dozen sheets of paper, numbered and folded to the first step, the second step, the third step…all the way to the finished box.

“They might not like it enough,” he fretted. “Even with the diagrams, it might not be good enough. Maybe it’s already been done and they’ll think I’m a copycat. But I’m not. This was a vision. I didn’t find this in no book. Still, it’s not like a stegosaurus or a Easter lily. It’s just a box. They may not like it.”

As it happens, they liked it enough to find a volunteer to create the diagrams so they could include it in the 1990 Annual Collection. I went to the convention that year, and when I taught Jack’s box, Lillian Oppenheimer herself pronounced it a poem, a marvel, a significant accomplishment.

Jack was thrilled, but he couldn’t believe it. Neither, it seems, could any of his family members or the people he lived with. Not until he received his copy of that big orange book, and there it was.

Jack was thrilled, but he couldn’t believe it. Neither, it seems, could any of his family members or the people he lived with. Not until he received his copy of that big orange book, and there it was.

He had known from the gitgo that this self-closing box was, indeed, all that. But still — when you can hear it in their voices that your housemates and your mom and your old fourth grade teacher are impressed, that’s pretty sweet.”

“I’m a published origamist.”

Although he called me every two days without fail, he only came to my house once. About a year after we met. Right after I finished library school. The day before I moved away.

I told him we could fold paper together one last time, as a way of saying goodbye.

He stood in the living room and looked all around my empty house – through the dining room into the breakfast nook, into the front bedroom, down the hall.

“So this is where you been all the whole time we was talking on the phone.”

We sat on the floor with a stereo carton between us, and he showed me whatever it was he had just come up with.

After about an hour, he looked at his watch and said, “I need to let you go.” He stood. “So I guess this is goodbye.”

I said, “You have my new phone number in Virginia. We can still talk. It won’t be all that different.”

“They got long distance blocked at my house.”

“Then call collect. Saturday and Sunday mornings the rates are low. I can afford a call a week.”

He turned to leave, then he turned back to me one last time.

“You want a goodbye hug?”

“Nah. How ‘bout a handshake?”

He still had no grip. But his palm was dry.

I left Oklahoma City on a Sunday, and in Fredericksburg, Virginia, the next Saturday morning at 8:00 the phone rang with a collect call from … “Paperman Jack.” At thirteen hundred miles it was no different than it had been at six blocks.

“Hi, Megan, guess what I figured out today?”

Every Saturday morning that I was home to answer the phone, Jack was as good as an alarm clock. For thirteen years.

I’d get a little news – his group house lost funding and everybody was on their own now; his social worker was helping him file for SSI benefits; he met an elderly lady on the bus and folded a flower for her, and she told him he should open a store and sell them, so he was looking into it. Then abruptly, he’d say, “Okay, I better let you go, I’ll talk to you next week.”

A couple of times a year I’d send him art supplies — glue, tape, new scissors, fancy paper clips, decent kami origami paper in bright colors, and (heaven forgive me!) googly eyes. For his birthday and for Christmas, if I had it, I’d send him $20, and with that he might treat himself to a couple of tools — needle-nose pliers, wire cutters for the coat hangers that were integral to many of his designs, a cafeteria meal ticket hole punch that made weensy little holes.

I kept him in postage stamps and pre-addressed labels so he could send me examples of the inventions he spoke of during our conversations. Every few weeks I’d get a lumpy enveloped in the mail, and I knew what our Saturday morning phone talk would be about.

I didn’t go back to Oklahoma very often, but whenever I did, we’d get together and … um … you know, fold some paper.

The first summer after I moved, he was living on his own in a cheap apartment downtown. I’ve only ever had a sketchy idea of why Jack lost his disability income. I think he was deemed fit enough to pay his own way in the world.

They did help him find a job. Whoever “they” ever were. And an apartment. Right downtown. At a time when nobody lived right downtown in Oklahoma City unless they absolutely couldn’t help it. Somewhere on 4th Street. I’ve driven past the place during visits home. Even in times of economic upturn, it’s still a wreck. When Jack lived there, Oklahoma’s economy was gasping.

But it was close to the job they found for him. He was on the cleanup crew at the convention center — maybe a half mile walk. He worked swing and graveyard, cleaning up after events like the circus and the national rodeo finals.

I don’t know if it was his co-workers or his neighbors. Or somebody else entirely. He wouldn’t tell me who. But it did weigh heavily enough on his mind that he told me what: While he was at work, some friends were using his place to meet up with hookers. To make drug deals. Sometimes they’d give him ten dollars for the use of his bedroom. Sometimes they’d give him a pack of cigarettes or a bucket of KFC. Or nothing.

He wanted it to be okay. Like he was running with the big dogs. But he was scared. And broke all the time now, too. Well. He was eating. And he still smoked a pack a day. But he couldn’t afford his meds. And now the voices were talking to him. Telling him he was worthless. Telling him he should use his scissors — remember the long metal shears with the broken tip? — and poke his eyes out. Or stick the people that he knew were using him.

If there were resources to call upon from 1300 miles away, I was unaware of them. I asked, every time we talked, if he had told his social worker.

“No. I only got one appointment a month now. Besides, I ain’t no snitch.”

I said, “Listen. I know you’re not a snitch. But you have to tell someone. And your social worker is the one to tell, because social workers have to swear that they’re not snitches, either. So if you tell her, she can’t tell anybody else. What she can do is help you think of some ways to take care of yourself without getting hurt. And it’s just good manners, Jack, to let your social worker know if you’ve quit taking your meds. So she won’t get her feelings hurt when you start acting weird around her.”

Within a few weeks the SSI payments resumed, and he had moved to a little house on Northwest 20th Street. Too far to walk downtown.

Once, and I think it was only once, Jack called me in the middle of the week.

“Collect call from…”

“Paperman.”

“Will you accept the charges?”

“Yes.”

On a week night.

I thought, This has to be something serious.

It was.

“Hi, Megan, it’s Jack. I know I ain’t suppose to call in the middle of the week, an’ I’m sorry, but I might be in jail on Saturday so I wanted to let you know. Maybe it’s going to be awhile before we can talk.”

“Jack! What’s going on? What kind of trouble are you in?”

“Jack! What’s going on? What kind of trouble are you in?”

“I can’t say. My lawyer told me not to talk about it to anyone.

“Okay. That’s probably a good idea. Can you tell me, if you go to jail how long do you think you could be there?”

“I don’t know. A long time. I need to let you go now. I’ll call when I can. Bye.”

I want to say I stayed awake worrying about him, but I didn’t. A wave of vicarious dread swept through me and grabbed my throat whenever I thought about him at the mercy of a criminal justice system, incarcerated, warehoused, exploitable, discarded. But those waves were fleeting. I called his phone every few days and left messages. At least the phone hadn’t been disconnected. I slept fine. And a couple of Saturdays later, he called.

He never did tell me what his brush with the law was about. But it wasn’t long before he was living in another “sheltered” environment. This one was a deteriorating, decommissioned Best Western or Travelodge on Newport Avenue, near Portland and Northwest Highway. At the end of a cul-de-sac, within twenty yards of a busy limited access highway you had to drive a mile to enter. Who needs metaphors? A literal description says it all.

Some time in 2002, during a trip home, I visited him there. That was the time my partner, whose name is also Jack, met Paperman Jack.

Landscaping around the place consisted of weeds pushing through the asphalt parking lot. No trees. No shade. The nearest neighbor was a defunct little commercial strip. A mis-matched suite of white plastic patio chairs and metal folding chairs sat against the building’s front wall, and every chair was occupied by a man with a drug-induced hundred-yard stare. They slouched, they lounged, they hunkered. Smoking. Staring at traffic. And then at us as we walked past them. But with no more interest than they gave the traffic.

“Does Jack Knutson live here?”

“Who?”

“Um, Paperman?”

“Oh. Yeah. Look inside.”

“He’s got some art in there.”

Paperman was expecting us. It had been a couple of years since our last face-to-face. I had to do a double take to recognize the man standing in front of me. He was about fifty pounds heavier. He greeted me with a stiff half-hug and a smile full of awful looking brown teeth, a result of nicotine, bad hygiene, and no dental care for God knows how long.

“Hi, Megan. Look what I just figured out to make.”

During our weekly phone calls, I didn’t talk about “my Jack” all that much, even though on many of those Saturday mornings, he was right there, within earshot of half of the conversation. Sometimes he’d pick up the phone, accept charges, and say, “Hi, Jack! This is the other Jack. You doin’ okay? … I’ll get Megan for you.” Or he’d holler out, loud enough to carry from across the room, “Hi, Paperman! I loved your clown cards. But my personal life wasn’t what Paperman and I talked about.

Before that 2002 visit, I told Paperman that I was bringing “my Jack” to Oklahoma on this trip, and that “my Jack” would like to meet him. He said okay. Even so, when we showed up there at the repurposed Best Western, I could see that Paperman was ill at ease. But it’s not for nothing that people who know this man I live with often refer to him as Saint Jack. There’s not a more affable, curious, tolerant, kind human being on the planet. Within seconds they were talking shop.

“So, how do you get the bodies rounded and soft like this? It’s not all masking tape, is it?”

“Toilet paper! I found out where they store it. I got a endless supply.”

“Wow! They’re flexible. What gauge wire do you use for their skeletons?”

“Sixteen I think. Maybe eighteen. Megan sent me some.”

“She told me you did one of those thousand crane things.”

“It’s upstairs. With a bunch of other stuff. Wanna see?”

And so we were shown upstairs to Paperman Jack’s room. I kept looking around for someone in a nurse’s uniform to ask us to sign in or something. Kept expecting to be told only residents were allowed beyond a certain point. It didn’t happen.

His room was furnished with: a twin bed, particle board dresser, card table, folding chair, desk lamp. Daylight filtered in through a sticky nicotine haze over the single small window. The card table was littered with projects and art supplies — masking tape, duct tape, copy paper, scissors, wire cutters, made-in-China pliers. Brown plastic pill bottles — a lot of them — littered the top of the dresser. Apparently, Paperman was deemed compos mentis enough to administer his own meds.

Paperman’s 9/11 Memorial Senbazuru hung from the emergency sprinkler in the corner of the ceiling. I had never seen 1000 cranes altogether like that. It sent chills across my back. There was a statement taped to the wall nearby.

We had made plans to take him to lunch, and again, I expected someone with a clipboard to make us sign in and out. A woman in scrubs was cleaning countertops in the common room, so we announced our intentions to her.

“See ya later,” she said.

I wanted to take him someplace nice. Not fancy. But clean. Where the food was fresh and it tasted good. We took him to the Classen Grill, which looked as though it had fallen upon hard times since the last time I had eaten there. On the surface, it was a little down at the heels. But still, it was way too upscale for Paperman to feel comfortable there. I’m not sure he even tasted his world famous chicken fried steak. He sat hunched, looking down, like a kid expecting to be scolded, and he hardly talked. I kicked myself. Denny’s would have been fine. IHOP. Waffle House would have been perfect.

After lunch, we asked if he wanted to go anywhere in particular. He didn’t. So we took him back to the motel. I dug out from the cavern of my purse the Care Package I had assembled that morning at Home Depot — several colors of duct tape and masking tape, more 18 gauge steel wire, and a good needle nose plier/wire cutter.

Hugs were always awkward, so we just shook hands.

“I’ll let you go now. Talk to you next week.”

And that’s the last I saw of Paperman Jack.

It was February, 2003. Sunday evening. Coming in the door from a weekend gig, I could see the message light blinking on my telephone. Four calls, all from the same number in some area code I was unfamiliar with, spanning Friday evening to Sunday morning.

“This is (someone whose name I didn’t recognize). Would you call me please? It’s kind of urgent.”

“This is (that same person). I really need to talk to you.”

“I wouldn’t ask you to call if it wasn’t important. Call collect. I’ll pay for it.”

“I’m Jack Knutson’s mother. I’d really appreciate it if you’d call me back. I won’t take much of your time.”

I stood there in my coat, my bag still hanging off my shoulder. As I dialed, something told me to sit down.

“Hi. It’s Megan Hicks. I’ve been out of town. I only just this minute got your messages. Is Jack all right?”

She told me that Thursday morning, when he didn’t come down for breakfast, the housekeeper had found him dead in his bed.

“Of what!?”

“They’re sayin’ probably a heart attack. He let himself go. Got real fat there at the end. But really, there’s no tellin’.”

She said she had gone down to Oklahoma City to clean out his room.

“…and I found his address book, and there was your number in it. I thought you might want to know. I mean, for years now, whenever I talk to him it’s Megan this and Megan that, and, well, he just thought the world of you, so I thought you might want to know.”

I thanked her for calling. I told her I thought the world of her son. That he was one of the most remarkable people I had ever known.

“Well, he was something else, now wasn’t he?”

When I hung up, Jack touched my shoulder and asked, “Dead?”

I nodded. And while he sat on the footstool holding my hands, I sat in my big brown chair and told myself the news could have been so much worse.

That time when he called to tell me he might be going to jail, I entertained visions of Paperman locked up with people against whom he couldn’t defend himself — incarcerated, warehoused, exploitable, discarded. It was only several years later that it occurred to me that’s exactly what had happened to him.

I believe Jack Knutson died of criminal neglect. For months before and after our final visit, he talked about how he could only see his shrink once a month now, then every six weeks, then…every three months. His social worker had taken on so many more cases that she couldn’t see him as often, either. All those prescription bottles on top of his dresser! I wonder who knew exactly how much of what Paperman was taking? When was the last time his heart had been checked? His last blood work? Dental checkup?

The following Saturday morning I woke up disoriented at 8:00 when the phone didn’t ring. And then I remembered, Oh. That’s right. Paperman won’t be calling anymore. And I turned over and went back to sleep.

What Jack and I shared was a small friendship. It wasn’t deep, it wasn’t broad, but it had longevity. He was like a neighbor — someone you know for years by virtue of inhabiting common ground and probably wouldn’t know otherwise. Our common ground was a square of paper… because he and I both recognized the unlimited potential in that common, unremarkable, ubiquitous, disposable material. We both knew “the peace of paper.”

Jack Knutson taught me everything I need to know about making art. For thirteen years I had regular glimpses into the life of someone whose urge to create was so strong it overrode anti-psychotic drugs. His delight was in the creation, and once the creation was done he laid it down (or mailed it to me) and went on to create something else and something else and something else again. Maybe someday he’d be a famous “origamist.” Maybe someday he’d get a driver’s license and drive a car. Maybe someday he’d buy his mom a house where they could live together and she’d be proud of him. Til then, though, it was a thirteen-year string of Saturday morning announcements: “Hi Megan, it’s Paperman, guess what I came up with this time!”

Megan Hicks writes, makes art, and tells stories. Her storytelling credits include the National Storytelling Festival, regional festivals throughout the U.S., schools and libraries nationwide, and tours on three continents. Currently, she lives in Nether Providence, Pennsylvania, with the love of her life and three cats. [email protected] (540) 371-6775

Megan Hicks writes, makes art, and tells stories. Her storytelling credits include the National Storytelling Festival, regional festivals throughout the U.S., schools and libraries nationwide, and tours on three continents. Currently, she lives in Nether Providence, Pennsylvania, with the love of her life and three cats. [email protected] (540) 371-6775